A fortnight ago I was very lucky to be given the chance by one of my colleagues, Dr Thomas Birkett, to present part of a lecture to his third-year group studying in UCC’s School of English. The subject, or rather, object, of our lecture was Grendel’s Mother, the second monster that the titular Beowulf battles in the Old English poem. The lecture discussed Grendel’s Mother in the wider context of feminine monstrosity by evaluating Anglo-Saxon perceptions of the “correct” way in which to perform femininity, where Grendel’s Mother is perhaps considered monstrous by the poem’s Anglo-Saxon audience because she performs her motherhood in a masculine manner. (She does this by avenging her son, who Beowulf slays by ripping his arm off: Jane Chance gives a convincing argument as to why this behaviour is considered monstrous by a female figure).

During Dr Birkett’s closing part of the lecture, he briefly discussed the depiction of Grendel’s Mother in the latest Beowulf film (dir. Robert Zemeckis 2007), focusing on the digital stylization of Grendel’s Mother’s (Angelina Jolie’s) body. The poet provides us with very little physical description of either Grendel or his Mother, which has given both translators and film-makers a lot of artistic licence in their portrayal of the creatures. Zemeckis’ film is no different in this regard, but, while modern translators of the Beowulf text such as Seamus Heaney have emphasised Grendel’s Mother’s monstrous elements, Zemeckis’ film sexualises her.

The modern Grendel’s Mum is still, however, monstrous. Whether the director’s intention was to demonstrate the monstrosity of the highly sexualised female image (unlikely), or to garner a teenage male audience (more likely), the film’s representation of Grendel’s Mother reminded me almost immediately of another monstrously sexual femme fatale, Star Trek: Voyager‘s Seven of Nine.

Seven of Nine, Tertiary Adjunct of Unimatrix Zero-One, known to her colleagues aboard the USS Voyager as Seven of Nine, or, affectionately, as Seven, wears a skin-tight catsuit, and, like Jolie in Beowulf, a pair of high heels that emphasize her curves. Seven was a Borg drone who was severed from the collective and encouraged (it must be added, against her will) to become human once more. Seven’s reintegration into humanity is arguably what made a dull series a lot more interesting, and, watching her learn to become human again also makes us question things we take for granted as humans.

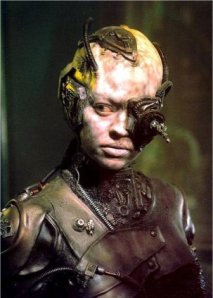

However, like Grendel’s Mother in Zemeckis’ film, Seven’s sexualisation happens at almost a cost to her monstrosity: the Borg collective really aren’t a pretty bunch and neither was Seven when she first encountered the Voyager crew, at least in any standard (human) sense of beauty.

Seven is also not the only female character in the series to have been beautified: the half-human half-Klingon B’Elanna Torres is a sexier version of the alien Klingon (at least as far as humans are concerned), the kind of Klingon you’d want to go to bed with.

http://www.fanpop.com/

B’Elanna in her usual form as a human-Klingon hybrid

http://www.loganspocky.fr/

B’Elanna as a Klingon, after an alien doctor separates her Klingon and human DNA

This is precisely the point that I’ve been trying to get to: the monstrosity that male monsters such as Grendel, or a male Borg drone, embody doesn’t rest on “fuckability” the way female monstrosity does, at least in their depiction on the screen. This is important, as a woman’s “fuckability” has everything to do with what she looks like and these figures are constructed for a gaze that values them on this ability alone.

Focus on the sexuality of the monstrous feminine is nothing new -1950s B-movies such as Attack of the 50 Foot Woman and The Wasp Woman conflate the dangers of a sovereign feminine sexuality with anxieties surrounding impending nuclear war* -but I think that female sexuality is used in 2007’s Beowulf and Star Trek: Voyager as a way to diffuse the danger Grendel’s Mother and Seven of Nine impose on the masculine communities of each text.

What I mean is that their exaggerated sexuality is one which is imposed on these figures by a male gaze that gets to define what female sexual allure should be -tight-fitting clothing (or gold paint, in Grendel’s Mother’s case), high heels, perfectly-proportioned figures -and I think that this diffuses the danger either of these women pose. Seven of Nine is one of my favourite characters in Voyager; she makes me laugh, she makes me question some of my fundamentally core beliefs, she even makes me cry, but she doesn’t scare me, and much of that has to do with her sexualised image.

Shouldn’t monsters be (at least a little) scary? Isn’t that their point?

* I would like to thank Miranda Corcoran for this wonderful nugget of information and the immensely entertaining paper in which she explored this conflation.